Image from http://msrailroads.com

RICH SECTION OPENED.

First Train Over the Gulf and Ship Island Road Started.

ITS HISTORY FULL OF TRAGEDY.

Building of New Mississippi Line to New Gulf Outlet Attended by Series of Fatalities — Killing of Gambrell by Colonel Jones S. Hamilton, The Adams – Martin Duel.

The first train over the new road to the gulf of Mexico — the Gulf and Ship Island — left Jackson, Miss., at 6:30 the other morning, reaching the terminus, Gulfport at 2 o’clock, says the Chicago Times-Herald. A number of state officials, together with officers of the road, made the trip. At Gulfport a banquet was given in the evening, and many speeches were made that predict a future for the new seacoast city. Gulfport is nothing more than a village now. At Jackson, the northern terminus, connection is made with the Illinois Central and the Alabama and Vicksburg branch of the Cincinnati Southern road. It is believed that the Gulf and Ship Island will eventually be extended to Memphis, and when that is done the expectation is that some of the grain trade of the northwest will be sent abroad via Gulfport.

The road passes through a section of the state that is new to civilization. Many of the inhabitants along its line had never seen a locomotive engine until the work trains appeared and awakened echoes from the hills which had heretofore caught only the cries of the wildcat, the dying groans of feudists and the piercing crack of the huntsman’s rifle. The road passes through a portion of Jones county, which seceded from the Confederacy during the civil war and set up an independent government. It traverses Wayne county, which has fewer Bibles per capita than any other county in the nation. It splits Green county almost in twain, and some of the roadbed is made of dirt on which the notorious Murrell and Copeland gang of murderers and outlaws made their rendezvous for a decade.

Image from http://www.samlindsey.com

The road opens to the lumber trade a virgin pine forest. It is estimated that within the next five years more than 1,000,000,000 feet of timber will go to the north on cars hauled by this new line. The land adjacent is favorable for raising fruits and grapes, but it has never been cultivated. Not a painted house is to be seen between Jackson and Gulfport. The inhabitants for the most part have existed among themselves without having come in contact with the outside world. The road will make the work of the revenue agent less perilous. Illicit distilleries have flourished for years unmolested in much of the territory because officers have been afraid to penetrate its ravines, hollows and hillsides.

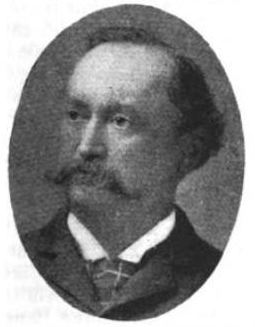

The history of this road has been attended by more tragic deaths than that of any other enterprise started in the south since the civil war. Twenty-five years ago Colonel Jones S. Hamilton married one of the belles of Mississippi, Miss Fanny Buck. Their first child was a son, and he was named for his father, John S. Jr. On the day of the child’s baptism Colonel Hamilton said to his wife that he would build a railroad, that his heir might become its president when he had attained his majority. Colonel Hamilton selected the terminal point, and Mrs. Hamilton gave Gulfport its name. Twenty-four hours after the last spike had been driven which made the road complete between these two points Jones S. Hamilton, Jr., was killed by the cars in the yards at Jackson. That was a few weeks ago. Colonel Hamilton still holds an interest in the railway company, and it was his son’s aim to escort a number of his young friends to Gulfport on the train the other day.

Instead his grave received new flowers from those he expected to entertain.

In 1884, after a survey of the road had been made, Colonel Hamilton interested Chicago capital in pushing the road to completion. At the time he was lessee of the state penitentiary, a state senator, chairman of the executive committee of the Democratic party and the wealthiest man in the state. His home, Belhaven, was the most magnificent in the country. It sat on an eminence two miles from the statehouse and contained 600 acres in flower yards, tennis courts and fishing pools.

His reputation for lavish hospitality was known throughout the south.

Image from http://www.rebelstatescurrency.com

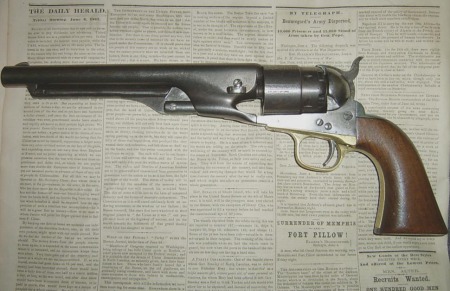

In his political affairs Colonel Hamilton encountered the bitter opposition of John H. Martin, a descendant of Chief Justice John Marshall; T. Dabney Marshall, a literary and art critic, and Roderick Dhu Gambrell, who were the leaders of the prohibition movement. Bitter personalities were exchanged, and Hamilton was challenged by Gambrell to fight a duel. Attacks on Colonel Hamilton continued, and in May, 1886, he and Gambrell met on the bridge which divides East from West Jackson. There were no eyewitnesses to what followed, but when the crowd got to the place, having been attracted by shots, Gambrell was dead, and Hamilton was seriously wounded.

The affair caused great excitement. There was talk of lynching Hamilton, and the residents, about evenly divided between the factions, came so near to a clash that a call for the militia was necessary. Meantime Gambrell’s picture was being sold throughout the civilized world. Boxes of them were shipped to Australia and to Africa. Miss Frances E. Willard started a subscription for the purpose of assisting the prosecuting fund.

After spending a year in prison Colonel Hamilton was acquitted, his release being celebrated by a remarkable demonstration of rejoicing, in which Hamilton was brought into the city in a carriage drawn by 100 prominent residents. The week before the end of the trial, however, General Wirt Adams and John H. Martin killed each other under most sensational circumstances as the result of the proceedings. General Adams had testified to Colonel Hamilton’s good character and was attacked by Martin in his paper. Adams and a friend went to Marin’s office. The offensive article was pointed out, and Martin said he was responsible for its appearance — in fact, had written it.

“Then are you armed?” asked General Adams. Martin said he was not. Pulling out his watch, General Adams replied: “It is now 10:35. I will give you until 11 o’clock.” Martin ran for his home, four blocks away, while Adams took a position across the street from Martin’s office. Ten — 25 minutes passed. Then Martin showed himself around the corner. Adams advanced to meet him. When the two were within 40 feet of each other, they began firing. The first bullet struck Martin in the thigh and knocked him down. General Adams continued advancing. Martin had recovered from the stun and was firing with deliberate aim. At the third shot from Adams’ pistol Martin fell backward, mortally wounded.

Adams had one ball remaining, and he walked to where his enemy lay and looked down at him. Martin, too, had one bullet in his pistol. Meantime General Adams had been untouched. Two shots rang out simultaneously, and General Adams fell, his face striking the pit of Martin’s stomach. When the officers reached the spot, both were dead. Colonel Hamilton came out of jail with his vast estate heavily incumbered. A government land grant made to the road had been forfeited, but this was recovered through the efforts of Secretary James G. Blaine, to whom Hamilton had gone to school in Kentucky.

A little while after Hamilton killed Gambrell, a railroad tie contractor of the name of Purvis killed a man of the name of McDonald, was convicted and sentenced to be hanged. On the scaffold Purvis denied his guilt. When the know was adjusted and the trap sprung, the rope slackened, and instead of Purvis being suspended in the air he fell to the ground. In the excitement the execution was delayed, and on Purvis’ claim that he could not be resentenced because he already had been legally hanged the case became one of the most noted in the history of the state. Purvis eventually was pardoned, and he is now in the woods along the line of the Gulf and Ship Island railroad getting out bridge timber.

Active work on the Gulf and Ship Island was resumed five years ago. About the time it seemed certain that it would be pushed to completion Colonel Hamilton fell down his steps, receiving wounds which practically have made him helpless ever since. He is little better than an invalid.

Gulfport is on something of a boom. The harbor is a natural one and will require little money from the national government. It is almost midway between Mobile and New Orleans and is touched also by the Louisville and Nashville railroad. The fact that it is the terminal of the Gulf and Ship Island will make it an important lumber shipping point for years to come. Many sawmills, canning factories, storehouses and residences are already in the course of construction.

Sandusky Daily Star (Sandusky, Ohio) Sep 5, 1900

The image and a biography of Jones S. Hamilton can be found on Google at the following link:

Title: Mississippi: Contemporary Biography

Volume 3 of Mississippi: Comprising Sketches of Counties, Towns, Events, Institutions, and Persons, Arranged in Cyclopedic Form, Dunbar Rowland

Editor: Dunbar Rowland

Publisher: Reprint Co., 1907

pg 311

Read more about the Gambrell incident in my previous post, Roderick D. Gambrell: Death of a Hip Pocket Reformer.

Tags: 1900, Duel, Gullfport MS, Jackson MS, John H. Martin, Jones S. Hamilton, Mississippi, Newspaper Editors, Prohibition, Railroad, Roderick Dhu Gambrell

October 18, 2010 at 8:26 pm |

[…] White Cap Swings…but Lives By mrstkdsd Will Purvis was mentioned in my Colonel Jones Stewart Hamilton: The Train and the Tragedies post, although the finer details were a bit mixed up. The victim was Will Buckley, not someone […]

November 18, 2014 at 3:12 pm |

Thanks for posting this information. I am writting a self-guided walking tour for the Capital St. area of Jackson, MS. and was looking for information on the Hamilton-Gambrell, and Adams-Martin affairs and had not been able to find a lot of info.

Thanks again-can’t wait to start following “YesterYear ONce More” Is there an archive of past posts?

November 18, 2014 at 9:32 pm |

The walking tours sound awesome. Glad you found this useful.