Chief Cornplanter image is from the Salibury, PA webite.

Chief Cornplanter image is from the Salibury, PA webite.

[From the Attica Telegraph.]

A Reminiscence of Border Life.

In the dark days of our Revolutionary struggles, there lived many brave, noble and generous men, who did much toward achieving the independence of this now prosperous and happy nation, by acting singly, or with a chosen few upon whom they could place the utmost reliance. This mode of warfare, though carried on in a comparatively small way, was far more efficacious, in proportion to the numbers engaged in it, than the operations of the largest bodies of soldiers who fought in the fort and open field. It did not generally accomplish much n a single occasion, but was constantly at work either acting on the offensive, or furnishing information to the head-quarters of the American army. This, in fact, was the only way by which the hostile tribes of Indians could be effectively punished for their wanton and malicious depredations. Every reader is aware that they were instigated by the British to perpetrate deeds the most shocking and revolting to humanity. Tradition has handed down the names of numerous individuals, unrecorded in the history of our country, who were celebrated for many valorous deeds, the remembrance of which seems fast disappearing “through the dark vista of bygone years.” An incident in the eventful life of one of this class is the subject of our narrative. We will endeavor to give the substance of it, as it fell from the lips of one of the “[oldest inhabitants]” in our hearing.

Of Joseph Brady’s birth, parentage, &c., our “informant” does not enlighten us. Suffice it to say, he was a brave and magnanimous warrior, and the commande of a small band of men, of his own school who were employed against the indians in Western New York and Pennsylvania. Although destitute of an education, having grown up in the “backwoods,” our hero had learned much from the school experience, and was skilled in that knowledge which was most essential to him in the station he was called to occupy. It is said that he could converse fluently in at least twenty of the different languages or tongues spoken by the tribes of the Atlantic states. This, to him, was an invaluable acquisition, and the sequel will show the advantages which it gave him over the Indians.

Six Nations’ map is from the Access Genealogy website.

Six Nations’ map is from the Access Genealogy website.

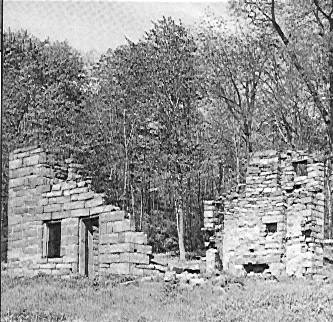

Cornplanter, whose name is celebrated as an Indian warrior, and the praise of whose greatness has been the theme of many a writer, was then the Chief of a small tribe whose village was situated on the western bank of the Allegany River, six miles below the boundary line between New York and Pennsylvania. The remnant of his tribe still remain there, possessing a fertile tract of alluvial land several miles in length, and extending from the river back to the Allegany Mountains, a distance varying from one to three miles. On the opposite side of the river, a high mountain rises abruptly from the water’s edge, and is covered with a thick growth of forest trees. The scenery about this place is wild, romantic and beautiful; although the “rapid march of civilization” is robbing nature of her former grandeur and beauty. What a contrast between that olden time and the present! The? those deep waters bore upon their broad bo?om naught but the light Indian canoe, and the white man dared not be seen, unguarded, anywhere in their vicinity.

Cornplanter and his “braves” had made an incursion into one of the nearest settlements of the whites, in which they had met with great success. Several of the unfortunate inhabitants fell beneath the murderous tomahawk, their buildings were consumed by fire, and a number carried into captivity. When the Indians arrived at their village with the prisoners it was determined that they should be burned at the stake. Accordingly, the time was appointed for this dreadful work, and the whole tribe were to be assembled to participate in it. The Indians were patiently waiting for the time when they were to glut their vengeance upon their “pale faced” prisoners, as they apprehended no fears that the whites were strong enough to attempt an immediate retaliation.

Brady heard of he sally made by Cornplanter upon the settlers, and determined to punish him severely for his cruelty. Accordingly, he and his men set out upon the expedition, and were soon in the vicinity of the Indian village, where they succeeded in capturing one of its inhabitants from whom they obtained all the information they wished, concerning the prisoners, and the time when it was intended to burn them.

Early in the evening on which was to terminate by the most dreadful death, the lives of a number of pioneers of his western region, Brady was occupying a secure position on the mountain, from whence he could perceive all that was taking place in the village below. Fires were kindled before all their dwellings until it was nearly as light as noonday. The woods to a great distance around resounded with the shouts of the savages, whose feelings were wrought up to the highest pitch of excitement. Brady waited until the captives were brought forth, and the Indians had commenced to bind them to the stakes. His heart beat high with the fear that he might be unsuccessful in his attempt to rescue them. But the long-wished for moment had arrived, and putting on the dress of the Indian he had captured, he boldly stepped forth into an open place where he could be distinctly seen from the other bank, and gave the shrill war-whoop peculiar to this tribe. He was immediately answered by the Indians, who supposed him to be one of their friends, just returning from an expedition similar to the one they were then rejoicing over. They inquired as to what success had attended him, to which he replied that he had taken a few prisoners but was unable to come over and join them that night on account of the wounds one of his men had received. He proposed that they should wait till the next day and then burn all the prisoners at one time. After some hesitation they complied with his request. The prisoners were taken back to their place of confinement, the fires extinguished, and soon a deathlike stillness succeeded the noise and confusion which had reigned during the former part of the evening.

Brady kept his position until after the “noon of night,” when he descended the mountain, and crossing the river, was soon in the heart of the village. The Indians had retired without leaving a guard, and the first intimation they had of the presence of a foe, was the bursting out of the flames from their houses, which were soon on fire in every direction. They rushed to their doors to be shot or cut down by the whites. A large number were killed or burned with the habitations, while the remainder escaped under cover of the night. Cornplanter fled and his village was entirely destroyed.

The prisoners were overjoyed to find that they were once more with friends who could protect, and without waiting even for the morning, started on their journey back to the homes of those who had rescued them. Brady lost not a single man while out on this expedition, neither were any wounded, and although he fought after the Indian custom, falling upon his enemies in an unguarded moment he achieved a great victory.

Cornplanter’s name has found a place in the history of those times, while Joseph Brady’s only reward was the consciousness of having performed a duty incumbent upon every American citizen in those days, that of defending his country, and the joy he experienced in being able to restore those whose fate was supposed to be sealed, to their homes.

Watertown Chronicle (Watertown, Wisconsin) Jul 28, 1847

NOTE: I couldn’t find anything more about Joseph Brady, but Wikipedia has an article about Samuel Brady, of “Brady’s Leap” fame, who had an Uncle Joseph Brady, who might have been him. Either way, I would imagine the two are at least related, as they were from the same area and were Indian fighters etc.

Greenville Treaty image from the Touring Ohio website.

Pennsylvanians, Past and Present

Cornplanter, Great Seneca War Chief and Friend of United States, Died February 18, 1836.

By FREDERICK A. GODCHARLES

(Copyright, 1925, by the Author)Cornplanter, the greatest warrior of the Seneca tribe, and a principal chief of the Six Nations from the period of the Revolutionary War to the time of his death, was born at Ganawagas, on the Genesee River, in New York, in 1722; he died at Cornplanter Town. just within the limits of Pennsylvania, Fedbruary 18, 1836.

Cornplanter was a half-breed, the son of a white man named John O’Bail, a trader from the Mohawk Valley. His mother was a full-blooded Seneca.

O’Bail is said by some to have been an Englishman, although Harris, Ruttenber, and others say he was a Dutchman Named Abeel.

All that is known of the early life of Cornplanter is contained in a letter to the governor of Pennsylvania, in which he says, “When I was a child I played with the butterfly; and as I grew up I began to pay some attention and play with the Indian boys in the neighborhood, and they took notice of my skin being a different color from theirs, and spoke about it. I inquired of my mother the cause, and she told me my father was a resident of Albany. I still ate my victuals out of a bark dish. I grew up to be a young man and married a wife, and I had no kettle or gun. I then knew where my father lived and went to see him, and found he was a white man and spoke the English language. He gave me vituals while I was at his house, but when I started to return home he gave me no provisions to eat on the way. He gave me neither kettle nor gun.

Historian Drake says Cornplanter was a warrior at Braddock’s defeat, July 9, 1755, and fought bravely as a French Ally.

During the Revolution he was a war chief of high rank in the full vigor of manhood, active, brave, sagacious and participated in many of the engagements in which the British employed their Indian allies.

Cherry Valley Massacre image from the Son of the South website.

He is supposed to have been present at the massacres of Wyoming and Cherry Valley, in which the Seneca took such prominent part. He was certainly on the warpath with Chief Joseph Brant during General John Sullivan’s expedition against the Six Nations in the autumn of 1779, and in the following year, under Brant and Sir John Johnson, he led the Seneca to their incursion through the Schoharie and Mohawk Valleys in New York.

On this occasion he took his father a prisoner, but with such caution as to avoid immediate recognition. After marching the old man some ten or twelve miles, he stepped before him, faced about and addressed himself to his father. He gave him his choice of following his yellow son, in which he promised him food and raiment or return to his fields and his white children. O’Bail chose the latter and Cornplanter gave him safe conduct back to the trading post.

Cornplanter was one of the parties to the treaty made at Fort Stanwix, October 23, 1784, when the whole of the present Northwestern Pennsylvania was ceded by the Indians to the Commonwealth. He also took part in the Treaty at Fort Harmar in 1789.

His sagacious intellect comprehended the growing power of the United States, and that Great Britain had forsaken the Seneca. He threw his influence in favor of peace.

During all the Indian Wars from 1791 to 1794, which terminated with General Wayne’s treaty, Cornplanter pledged that the Seneca should remain friendly to the United States.

He was a signer of the treaties of September 15, 1797, and July 30, 1802. These acts rendered him so unpopular with his tribe that for a time his life was in danger.

On March 16, 1796, Pennsylvania granted Cornplanter a tract of 640 acres in the present Warren County, to which place the old warrior retired and devoted his energies to his own people.It is said that in his old age he declared that the “Great Spirit” told him not to have anything more to do with the whites, nor even to preserve any mementos they had given him. Impressed with this idea, he burned the belt and broke and elegant sword that had been given to him.

A favorite son, who had been carefully educated, became a drunkard, thus adding to the troubles of Cornplanter’s last years.

He received for a time, a pension from the United States of $250 a year.

At the time of his death he was 105 years of age. A monument erected to his memory on his reservation by the State of Pennsylvania in 1866 bears the inscription “aged about 100 years.”

New Castle News (New Castle, Pennsylvania) Feb 18, 1925

*****

This bank advertisement ran in the newspaper for several days:

Indiana Evening Gazeete (Indiana, Pennsylvania) Oct 17, 1921