LOUISIANA ROMANCE.

—–

History of the Purchase of the Great West from the French Emperor.

—–

NAPOLEON WANTED A FRIEND

—–

Rather Than See England Have the Territory He Would Donate It to America — Purchase Proposed by Him.

—–

New York Commercial Advertiser.

There is an incident in American history that is as full of startling features, or even romance, as anything that ever transpired in a nation’s existence, and it is doubly interesting at this time when Hawaii is knocking at our doors for admission. It involves the circumstances of the Louisiana purchase, a mighty transaction, which gave the young republic “Louisiana and all that portion of the American continent extending northward to the tides that flow into the Pacific.” In detail these words meant Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Nebraska, Minnesota — that portion west of the Mississippi river — nearly all of Kansas, both the Dakota states, the Indian Territory, the greater part of Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho and Oregon — in all 900,000 square miles.

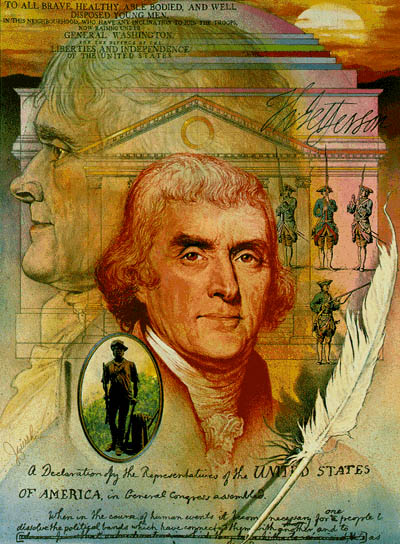

Image of James Monroe from Archiving Early America

For the incidents in this narrative that relate to the American part, the writer is indebted to Gen. George W. Monroe, a near relative of President Monroe, who permitted extracts to be made from letters written by his distinguished kinsman, our minister to France, when the Louisiana purchase was effected, and on the French side to data from the memoranda of M. Cambaceres, the close friend of the Vicomte de Saint-Denis whose grandson allowed the papers mentioned to be examined.

The treaty of Amiens, made in March, 1802, between France on the one side and Great Britain, the Batavian republic and Spain on the other, did not long endure. It was ruptured in May, 1803. Foreseeing its disruption, England, the mistress of the seas, began hostilities by seizing everything French on the ocean that she could. The work was commenced even before the breaking of treaty relations between herself and France. The latter country had no adequate means of retaliation at hand. Her fleet was totally unequal to that of Great Britain, and while the army of France was fairly capable and effective, nobody knew better than did the First Consul Napoleon that the arms were as obsolete as the tactical and the method of organization. But it was in money that France was most lacking.

The embargo against England had greatly damaged the trade in woven fabrics with that country and the wine merchants of south France so clamored that Napoleon was compelled to make his edicts less rigorous to them.

Meantime Great Britain was preparing for a death grip with the hated Corsican. It was not a time when great national loans were a feature of finance. Where the money to float his immense schemes was to come from the ruler of France could not tell. He needed 100,000,000 francs, not in assignats, but in gold, something all Europe would recognize as beyond question. This was the condition of France’s master Jan. 1, 1803.

The first consul was absorbed, preoccupied. He had directed that attendance of Cambaceres, the archchancellor, and Lebrun, Lord Treasurer of France, for that evening. He wished to discuss the money question with them. Bonaparte had many very unusual qualities, but one which was unique in his great character. He never asked for advice. “Relate to me,” he would say to an official, “the precise conditions with which I must contend. I will find the means to deal with them.” And he always worked the problem out alone.

A dispatch that day from Admiral Villeneuve (who was in command of the French fleet then cruising in West Indian waters) contained very disquieting information. It informed the Minister of Marine, and through him Napoleon, that from a sure source he had learned of England’s intention to attack France through her colonies, and the first blow would fall upon the thriving young City of New-Orleans. The information had been conveyed to the American Minister, Mr. Monroe, who was to have audience with the First Consul Jan. 3 and consider what steps the two nations might jointly take to ward off the threatened blow. IT was almost as great a peril to the young Republic as it was to France. With the mouth of the Mississippi River in possession of France’s hereditary foe and the bitter enemy of the sixteen States constituting the American Union, the great tide of commerce then setting southward from Pittsburg to the sea would be suddenly cut off or greatly injured and restricted.

Up to this time the commercial conditions between the two countries had been of the most liberal nature. France had made to our enterprising tradesmen southward concessions of the fairest and most friendly character. New-Orleans, indeed, was a free port to inland commerce, which was in the hands of Americans alone. This liberality was creating the Cities of Cincinnati and Louisville, and the smaller river towns were thriving. It was making the young West rich. Should all this prosperity be checked in a day? “Do everything in your power,” wrote President Jefferson to our Minister at Versailles, “to protect and foster the inland trade of our people with the Southwest.”

“I will see if the Americans cannot help us,” said Cambaceres, as he was taking leave of the First Consul that evening.

Image from KNOWLA

“Do you know, I have been thinking of that, too,” replied Bonaparte, as he placed his fine, white hand on his former colleague’s shoulder. “I have something in my mind that may change the fortunes of France. Do not speak to Mr. Monroe until my audience with him, which will be after the morning levee is over Jan. 3.”

Unfortunately, Mr. Monroe at this time did not understand the French language well enough to follow a speaker who talked as rapidly as did Bonaparte. So the intervention of an interpreter was necessary.

“We are not able alone to defend the Colony of Louisiana,” the First Consul began. “Your new regions of the Southwest are almost as deeply interested in its remaining in our hands as we are in retaining it. Our fleet is already not equal to the needs of the French Nation. Can you not help us to defend the mouth of the Mississippi River?”

“We could not take such a step,” said Monroe, “without a treaty offensive and defensive. Our Senate is really the treaty making power, and it is against us now. The President, Mr. Jefferson, is my friend as well as my official superior. Tell me, General, what have you in your mind?”

Napoleon did not at once reply. He was walking the room, with his quick, nervous step. It was a small private consulting cabinet, adjoining the Salle des Ambassadeurs. The great man had his hands lightly clasped behind him, his head inclined forward, his usual position in deep meditation. “I acquired this great territory, to which the mouth of the Mississippi is the gateway,” he finally began. “I have the right to dispose of it if I will. France cannot now defend and hold it. Rather than see it in England’s hands, I would give it to America. But why will your country not buy it from France?” There Bonaparte stopped.

In a second Mr. Monroe’s face was like a flame. What a diplomatic feat it would be for him! What a triumph for the Administration of Jefferson to add such a territory to the Nation’s domain! The Southern Senators and members, with those of Pennsylvania, whose City of Pittsburg was doing a great Southwest trade, would favor the purchase, for the production of cotton was beginning to be immensely profitable. All the really valuable cotton land not in the States already was in the territory mentioned.

Image from IMSA

The purchase would strengthen the South beyond words. Then, too, the United States would control the Mississippi River, which now drains twenty-three States. And he — James Monroe! What a place would his be in his country’s history! His name would be linked indissolubly with the creation of a new national domain. Already had Virginia given to the Republic the immense Northwest Territory — now comprising the States of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, part of Minnesota, and all of Wisconsin. Then she had followed this bestowal of a kingdom by the gift of Kentucky, the superb. And now — and now there came, for the third in the brief life of the Nation, an opportunity for him — a Virginian, too — to render as grand a service to the common country as had ever been given by any son — save one — that Virginia had borne or reared!

No man born of woman was a better judge of his fellows than Bonaparte. He read the thoughts of the man before him as though they were on a written scroll. He saw the emotions of his soul. “Well, what do you think of my plain?” asked General Bonaparte.

“The matter, Citizen General, is so vast in its direct relations to my country and what may result from it that it dazes me,” the Minister replied. “But the idea is magnificent. It deserves to emanate from a mind like yours.” Mr. Monroe spoke with deep feeling. He never flattered. The look of truth was in his eyes, its ring in his voice. The First Consul bowed low.

“I must send a special dispatch at once to President Jefferson,” said Monroe, “touching this matter. My messenger shall take the first safe passage to America.”

“The Blonde, the swiftest vessel in our navy, leaves Brest at once, with orders to the West Indian fleet. I will detain her thirty-six hours, till your dispatches are ready. Your messenger shall go on our ship,” the First Consul said.

“But how much shall I say the territory will cost us?” The great Corsican was just ending the conversation. It had been full tow hours long. He came up to the American Minister, and, after a moment, spoke:

“Between nations who are really friends there need be no chaffering. Could I defend this territory, not all the gold of the world would buy it. But I am giving to a friend what I cannot keep. I need 100,000,000f. in coin, or its equivalent in bullion. Whatever action we take must be speedy. Above all, let there be absolute secrecy and silence,” and Bonaparte bowed our Minister out. The audience was ended.

“Now, what can be going on between the master of France and the American?” asked Prince Metternich, the Austrian Ambassador, as he offered his snuffbox to his confrere and rival diplomat, Nesselrode. The dark-faced Russian shook his head as he daintily dipped his finger and thumb into the “Prince’s Mixture,” a famous snuff at that time.

Within the hour it was known to every Ambassador and Minister in Paris that Bonaparte had been closeted for two full hours with the American envoy, while Lord Whitworth, British Ambassador, with Metternich and Nesselrode, waited for an audience. Nothing but affairs the most urgent could have caused such a causerie. What could it mean? “I suspect it concerns England,” wrote Lord Whitworth that night to Addington, Prime Minister, in a confidential note, relating the incident; “but how or in what way I cannot perceive.” By the end of the week the circumstance had been communicated to the English Minister at Washington, with orders to keep a particularly close watch upon events.

Monroe wrote very fully of the matter to Jefferson and also to Nathaniel Macon of North Carolina. He knew Macon to be one of the ablest statesmen of his time. The negotiation was kept a profound secret until Mr. Jefferson and Mr. Macon could sound a majority of their own party in Congress. The New-England delegation alone made any active objection. Mr. Burr, Vice President, brought over New-York and Pennsylvania. “We have too much territory now to defend,” said Josiah Quincy of Massachusetts. Mr. Adams followed in the same strain. Indeed, mr. Quincy declared in the debate in secret session on this question that he the Louisiana Purchase, without his State’s consent, in his opinion, would justify Massachusetts in retiring from the Union.

Image from the International Napoleon Society

The main difficulty was for the United States to procure the ready money. Bonaparte had consented to reduce his demand to 75,000,000f. But this was no small sum to the struggling young nation, which needed money on all sides. The Revolutionary veterans were clamoring for arrears of pay, still due, and pensions. Then the country was trying to build a navy. It had the Ohio, the Indiana, and the Northwestern frontier to defend. Hard cash was dreadfully scarce. The Nation was land poor. But with Stephen Girard as chief agent, the then young Dutch house of Hope conducted the business to a successful ending, aided in London by their correspondents, the Barings — sons of old Franz Baring, a successful money dealer, whose successors had gone into banking. The accepted bills for 25,000,000f. at four months, drawn against the United States Treasury, bearing 6 per cent. interest, were sold at par. They were divided into sums of 50,000f. and 100,000f. for the convenience of purchasers. When the London bankers learned that the Dutch capitalists were quietly purchasing these bills, two brokers, representing the Bank of Scotland and the Rothchilds respectively, offered to take one-half the sum total. But the bills were already placed. Their bids were declined.

It was a great stroke of business for Stephen Girard. He made about $100,000 in commissions alone. It led to his appointment to be naval agent for the French fleets in the United States, an office of great dignity and profit, for he was the person with whom the French Government places its money for the maintenance of its fleets on the North American and West Indian stations. So it happened that Mr. Girard had always on hand great sums in gold, subject to the orders of the commanding officers of the French fleets on the stations named.

In many ways the Louisiana purchase was a good diplomatic stroke for our country. It gave the United States a credit and standing abroad that has never been lessened or lowered. IT was the re-creation of France. The First Consul had long seen the need of rearming and reorganizing the forces of that country. He summoned the most expert arm-makers in France and said: “I wish you each to furnish me with a model musket, the best pistols for horsemen, a musquetoon, [our carbine,] and a sabre after a model to be given you. I wish the arms to be ready for a test in sixty days.” The result was the finest military firearms that had ever been known. The musket adopted weighed a little over nine pounds. IT carried a bullet eighteen to the pound. Its barrel was 42 inches, fitted with the bayonet that is still in use. The lock was extremely fine, and, with good flints, sure of fire. The French military firearms became famous all over the world. The recoil of the old Tower musket of England, and its equivalent on the Continent was so terrible that soldiers dared not fire it from the shoulder, but shot from the hip. The new arm of Napoleon burned four drams of superior powder, against six in the old piece. The trigger pull was reduced to that of the fowling piece of the time, and the new musketry drill prescribed a careful aim.

On Dec. 2, 1805, the French Army tested its new small arms and fire drill in actual battle, for the first time, at Austerlitz. The fire of the French infantry that day was so deadly that the allied armies could not stand up against it, nor answer it, and the new twelve-pounder, light field gun, also used in action for the first time that day, was a revelation to the Austrian and Russian Generals, in its rapidity of fire, ease in handling, and its new iron carriage.

“The re-equipment of our armies, which the money obtained by the sale of Louisiana made possible, gave the French soldier such confidence in the superiority of his weapons over those of his enemy that he became irresistible,” said Gen. de Lafayette, in 1824, to Gen. Schuyler of New-York and to President Monroe.

This country owes much to the royalist armies of France, but the debt was well-nigh paid with the money that made the Corsican the master of Europe and the French Empire the mightiest in Christendom. But if France won all Europe, the American Republic gained a new empire, the greatest ever attained by negotiation since diplomacy was a science.

The New York Time – Feb 13, 1895

Galveston Daily News – May 25, 1895