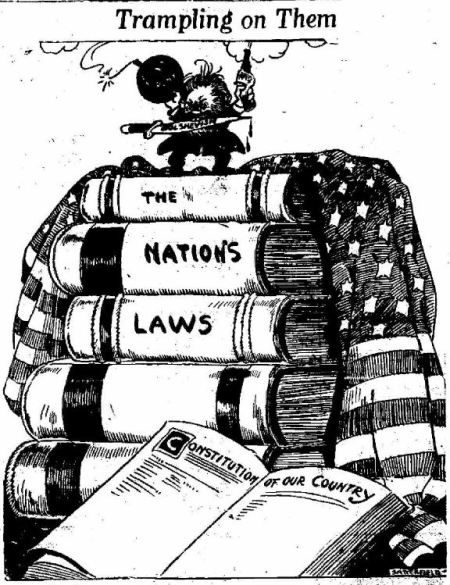

X-Raying The Constitution

The Constitution does not grant the Supreme Court specific power to declare legislation constitutional or unconstitutional. Nevertheless the court has declared many New Deal acts invalid. How has it gained this power? How has it exercised it through the years? Why have its decisions created a situation that has given rise to agitation for Constitutional change? In this last of his series on “Ex-Raying the Constitution,” John T. Flynn, NEA Service author-economist, reviews the history of the court’s domination over state and federal legislation.

_____

By JOHN T. FLYNN

(Copyright, 1936, NEA Service, Inc.)

A gentleman by the name of William Marbury, one day in the year 1800, filed a suit against James Madison, Secretary of State, to compel him to deliver a commission appointing him Justice of the Peace in Washington, D.C. Thomas Jefferson had just been elected President, sweeping the old Federalist party into the dust-bin. But the Federalists had several months left before inauguration to provide some jobs for “deserving” Federalists. Among others a law was rushed through setting up numerous judicial jobs. And on March 2, just two days before he was to go out of office, John Adams appointed William Marbury a Justice of the Peace under this law. He made many other appointments in this last hurry.

But the hurry was too much. Adams wanted to vacate the capital before Jefferson arrived. He wanted to snub Jefferson. And so in the haste of clearing out a terrible tragedy happened to poor Mr. William Marbury. His eleventh hour commission was not delivered to him. Many others failed to out. And when Jefferson came in he ordered them all cancelled. Marbury thereupon brought a mandamus action again James Madison, Jefferson’s Secretary of State, to force the delivery of the commission.

Jefferson resisted the suit, asserting that the Supreme Court had no power to interfere with the executive department. Thus the first great battle between President and Court was fought. And the case of Marbury vs. Madison became historic.

The tongues wagged, because it was felt John Marshall and his court would decide against Jefferson and that Jefferson would ignore the decision. But Marshall turned out to be too astute. He made one of the most cunning legal decisions in the history of the Court. Jefferson claimed the Court could not interfere with other departments of the government. But Marshall decided the case in favor of Jefferson and Madison. This is, he refused to order Marbury’s commission delivered. But he decided it on the ground that the congressional act under which Marbury was appointed was unconstitutional. Thus Marshall gave Jefferson the decision, but he did it by supporting the very principle which Jefferson so bitterly assailed. He asserted the right of the Court to declare an act of Congress unconstitutional.

That famous case — 136 years ago — settled that point and determined the whole course of our history. Because it is fair to assume that had Marshall held the Court could not declare laws unconstitutional, this would have been the end, as Senator Borsh had put it, of the inviolability of the written Constitution.

_____

And so it has been in the Supreme Court that all the great constitutional battles of the last 136 years have been fought.

As already pointed out, these battles have revolved around two great tendencies. One has been the effort of the central government to increase its power. The other has been the effort of the propertied groups to prevent the states and nation from exercising control over their affairs.

First let us look at the struggle of the central government to exercise wider power over national concerns, particularly in the economic field. It’s not a new fight. It didn’t begin with the New Deal. The federal government has sought to increase its field through the power of taxation, through the power to regulate commerce among the several states and with foreign nations and through its power over postoffices and post roads.

_____

One of the great weapons used by Congress to extend its power has been what is known as the commerce clause, under which Congress has power to deal with foreign and interstate commerce.

But in the last forty years countless battles have been fought over two points. What is commerce? What is interstate commerce? It was on this point the famous Schechter chicken NRA case was decided. The Court held that the poultry men in the case, while they handled chickens which were shipped in from other states, were not engaged in interstate commerce. When the poultry arrived at their plant, it was held there, handled there and the workers who did the work there were engaged in a business which was wholly within the state. Goods are in interstate commerce only when they are in “current” or “flow” not merely into the state, but into the state an on, with the manufacturer merely performing some function which is connected with this flow of the commodity in question.

Under this decision, a tremendous limitation was put upon the power of Congress to reach out and deal with various types of business on the ground that it is interstates.

Another weapon of Congress is taxes. Taxes were used in the AAA case. One of the first attempts to regulate industry through taxation was in the famous child labor cases.

The power to tax is the power to destroy. The courts have held that Congress can tax even to destruction. But the tax must be a legitimate tax — that is, for the purpose of raising revenue. Otherwise it would be invalid.

In the AAA cases, Congress attempted to tax processors to raise funds to pay benefits to farmers. This case also involved the power of Congress under the general welfare clause. This clause is frequently invoked to extend the power of Congress. In the famous AAA case, the Court held that Congress had no power to regulate agriculture, that under general welfare clause it could aid agriculture — that is give it benefits, but that if it attached conditions to the benefits, that could be regulating agriculture indirectly and that, therefore, the tax, imposed to aid this plan, was invalid. It was not a legitimate exercise of the taxing power.

_____

The other great series of battles about the Constitution have to do with the effort of organized business to prevent the states or Congress from interfering with it. These fights are made chiefly under the so-called “due process” clauses of the fifth and fourteenth amendments.

The first first on this subject came in 1875 in the famous Granger cases. States started regulating railroads rates. The roads held that fixing rates was equivalent to taking property from the roads and hence was depriving them of property without due process of law. The Supreme Court upheld the right of the States in this famous case — Munn V. Illinois, 113, U.S. This became then the charter for all our state regulatory commissions in the utility field.

But later the court began narrowing this view. It held that a New York statute prohibiting bakeries from employing men for more than 10 hours a day was a violation of the due process clause. It has held that commissions in fixing rates must allow utilities a fair return on investment or they will be depriving them of property without due process of law. It has held that laws fixing minimum wages for women and children are violations of the due process clause.

The Court has been holding that the federal government was encroaching on the rights of the states. These problems of regulation belonged to them — they were able to deal with them. One state — New York — tried to deal with one such problem — sweatshops and starvation wages for women in industry. It adopted a minimum wage law for women. Only a few weeks ago the Supreme Court held the law unconstitutional. It violated the due process clause. So the state, too, is as powerless as the federal government to deal with its economic problems.

_____

It is around these points — the commerce clause, the taxation power and the due process clause — that the New Deal measures have been argued. The court decided the “hot oil” case 8 to 1 against the New Deal; the railroad pension case, 5 to 4 against the New Deal; the AAA case 6 to 3 against the New Deal; the minimum wage law for women, 5 to 4 against the New Deal. It decided the rice millers’ case unanimously against the New Deal. The only cases won by the New Deal were the gold clause case and the TVA.

Two sets of reforms are being urged. One deals with the Court and is a plan to prevent the Court from declaring acts of Congress unconstitutional, save by a two-thirds decision.

The other plan suggests two amendments to the Constitution. The first would change the 5th and 14th amendments which prevents the government from passing regulatory laws because they tend to deprive men of property without due process of law. The other is to give the government outright jurisdiction of industry, corporations, power in all matters affecting the national economic welfare of the nation.

Around these measures, sooner or later, a great national struggle is certain to take place.