Image from the White River Valley Museum – Morse Code History

THE MAGNETIC TELEGRAPH.

BY MRS. E.L. SCHERMERHORN.

The following beautiful verses were received by us from Washington by the Magnetic Telegraph; and though the lightning speed with which they were transmitted, adds nothing to their beauty, it was a happy thought to select the wonderful invention, of which they are in praise, as the medium of transmitting them: — [Baltimore Patriot.

Oh! carrier dove, spread not thy wing,

Thou beauteous messenger of air!

To waiting eyes and hearts to bring

The tidings thou were wont to bear.

Urge not the flying courser’s speed,

Give not his neck the loosened rein,

Nor bid his panting sides to bleed,

As swift he thunders o’er the plain.

Touch but the magic wire, and lo!

Thy thought it borne on flaming track,

And swifter far than winds can blow,

Is sped the rapid answer back.

The sage who woo’d the lightning’s blaze,

Till, stooping from the summer cloud,

It played around with harmless rays,

By Fame is trumpeted aloud.

And sure she has a lofty meed

For him whose thought, with seraph reach,

To language gives the lightning’s speed,

And wings electric lends to speech.

Nerved by its power, our spreading land

A mighty giant proudly lies;

Touch but one nerve with skillful hand

Through all the thrill unbroken flies.

The dweller on the Atlantic shore

The word may breathe, and swift as light,

Where far Pacific waters roar,

That word speeds on with magic flight.

Thoughts freshly kindling in the mind,

And words the echoes of the soul,

Borne on its wiry pinious, bind

Hearts sundered far as pole from pole.

As flashes o’er the summer skies

The lightning’s blaze from east to west,

O’er earth the burning fluid flies,

Winged by a mortal’s proud behest.

Through flaming cherubs bar the gate,

Since man by tasting grew too wise,

He seems again to tempt the fate

That drove him first from Paradise!

Daily Sentinel and Gazette (Milwaukee, Wisconsin) May 18, 1846

The Electro-Magnetic Telegraph.

Some remarkable experiments have been made with Morse’s Electro-magnetic Telegraph arrangements, and they have demonstrated surprising facts. Wires extending in length 158 miles were laid down, the Battery, &c., prepared, and matters communicated that distance in almost a second of time! In experiments to ascertain the resistance to the passage of the electric current it was proved that this “resistance increases rapidly with the first few miles, and less rapidly afterwards, until for very great lengths no sensible difference can be observed. This is a most fortunate circumstance in the employment of electro-magnetism for telegraphic purposes, since, contrary to all other modes of communicating intelligence, the difficulty to be overcome decreases in proportion to the distance.”

This is truly one of the wonders of the age.

Bangor Daily Whig and Courier (Bangor, Maine) Oct 26, 1843

Image from Encyclopedia Britannica Kids – Samuel F.B. Morse; Telegraph

THE MAGNETIC TELEGRAPH — ITS SUCCESS.

The miracle of the annihilation of space is at length performed. The Baltimore Patriot of Sunday afternoon contains the action of Congress up to the moment of its going to press — received from Washington by Magnetic Telegraph Despatch.

The Patriot says:

Morse’s Electro Magnetic Telegraph now connects between the Capitol at Washington and the Railroad Depot in Pratt, between Charles and Light streets, Baltimore. The wires were brought in yesterday from the outer depot and attached to the telegraphic apparatus in a third story room in the depot warehouse building.

The batteries were charged this morning, and the telegraph put in full operation, conveying intelligence to and from the Capitol. A large number of gentlemen were present to see the operations of this truly astonishing contrivance. Many admitted to the room had their names sent down, and in less than a second the apparatus in Baltimore was put in operation by the attendant in Washington, and before the lapse of a half minute the same names were returned plainly written. At half past 11 o’clock, A.M. the question being asked here, “what the news was at Washington?” – the answer was almost instantaneously returned — “Van Buren Stock is rising” — meaning of course that his chances were strengthening to receive the nomination on Monday next. The time of day was also enquired for, when the response was given from the Capitol — “forty-nine minutes past eleven.” At this period it was also asked how many persons were spectators to the telegraphic experiments in Washington? — the answer was “sixteen.” After which a variety of names were sent up from Washington, some with their compliments to their friends here, whose names had just been transmitted to them. Several items of private intelligence were also transmitted backward and forward, one of which was an order to the agent here not to pay a certain bill. Here however, the electric fluid proved too slow, for it had been paid a few minutes before.

At half past 12 o’clock, the following wan sent to Washington, “Ask a reporter in Congress to send a despatch to the Baltimore Patriot at 2, P.M.” In about a minute the answer cam back thus: “It will be attended to.”

2 o’clock, P.M. — The despatch has arrived, and is as follows:

One o’clock. — There has just been made a motion in the House to go into committee of the Whole on the Oregon question. Rejected — ayes 79, nays 86.

Half past one. — The House is now engaged on private bills.

Quarter to two. — Mr Atherton is now speaking in the Senate.

Mr. S. will not be in Baltimore to-night.

So that we are thus enabled to give to our readers information from Washington up to 2 o’clock. This is indeed the annihilation of space.

The Clipper of Saturday contains the following information regarding the construction and working of the Telegraph:

The wire, (perfectly secured against the weather by a covering of rope-yarn and tar,) is conducted on the top of posts about 20 feet high, and about 100 years apart.

We understand that the nominations on Monday next will be forwarded to Washington by means of this Telegraph. The following is the Alphabet used:

We have no doubt that government will deem it expedient to continue this Telegraph to Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, when its utility shall have been fully tested. When understood, the mode of operation is plain and simple.

American Freeman (Milwaukee, Wisconsin) Jun 15, 1844

THE LATE CONVENTIONS.

A brief notice of the proceedings of the Tyler and Locofoco Conventions, held in the City of Baltimore on Monday the 27th of May and the following days —

….. [excerpt]

The Convention met again at four o’clock; when, after listening to sundry speeches, they proceeded to ballot for a candidate for the Vice Presidency, which resulted in favor of Silas Wright, of New York, who received 258 votes, and Levi Woodbury, of New Hampshire, 8. Information of his nomination was immediately communicated through the magnetic telegraph, to Mr. Wright, then at Washington City, who immediately replied, that [he could not accept] — eleven minutes only being taken in forwarding the information, and receiving the answer.

Alton Telegraph and Democratic Review (Alton, Illinois) Jun 15, 1844

THE MAGNETIC TELEGRAPH

On Thursday, the 23d ult, says the New York Commercial, the experiment of carrying the wires of the electro magnetic telegraph across, or rather under the East river, was made with perfect success. The lead pipe through which this communication is made, weighs over six thousand pounds, and was laid at the bottom of the river from a steamboat employed for the purpose, though not with out great risk and labor. It is one continuous line, more than half a mile in length, without joint. Through this extensive line of heavy pipe are four copper wires, completely insulated, so as to insure the transmissions of the electro magnetic fluid. We understand that the various routs north, east, and west, have been delayed at the intervening streams, for the purpose of learning the result of this experiment. The whole work had bee effected under the superintendence of Mr. Samuel Colt engineer and of the proprietors of the New York and Offing Electro Magnetic Telegraph Line — Repub

Alton Telegraph and Democratic Review (Alton, Illinois) Nov 8, 1845

Image from The American Leonardo: A Life of Samuel F.B. Morse

The late experiment of carrying the wires of the Electro-Magnetic Telegraph across, or rather under, the East river, New York, which was at first supposed to have been entirely successful, seems to have failed — the pipes through which the communication was made, having been brought up a few days afterwards, by the fluke of an anchor. Whether the attempt will be renewed, with such improvements as shall appear calculated to remove the cause of the failure, we are unable to say.

Alton Telegraph and Democratic Review (Alton, Illinois) Nov 15, 1845

It is said that the American Magnetic Telegraph proves more efficient than those used in England and France — the former giving sixty signs or characters per minute, and the English and French not over one-fourth of that number. The impressions made by the American invention are likewise better, and more permanent, than those produced by its European rivals.

Alton Telegraph and Democratic Review (Alton, Illinois) Sep 11, 1846

ANSWER

To the Enigma that appeared in the “Telegraph” of last week.

Maine, one of the United States.

Arctic, the name of an Ocean.

Greece, a country in Europe.

Niagara, a river in North America.

Egina, a gulf in Greece.

Thai, a country in India.

Imerina, a country in Africa.

Chili, a country in South America.

Tigre, a State in Africa.

Erie, a lake in North America.

Lima, a city in South America.

Elmira, a town in New York.

Green, a river in Kentucky.

Runac, a river in South America.

Aar, a river in Switzerland.

Parma, a country in Europe.

Herat, a country in Asia.

My whole is a Magnetic Telegraph, a great modern invention.

H.W.W.

Alton Telegraph and Democratic Reivew (Alton, Illinois) Aug 13, 1847

Image from Telegraph History

From the West Jerseyman.

THE MAGNETIC TELEGRAPH.

Along the smoothed and slender wires

The sleepless heralds run,

Fast as the clear and living rays

Go streaming from the sun;

No peals or flashes heard or seen,

Their wondrous flight betray,

And yet their words are quickly felt

In cities far away.

Nor summer’s heat, nor winter’s hail,

Can check their rapid course;

They meet unmoved, the fierce wind’s rage —

The rough waves’ sweeping force; —

In the long night of rain and wrath,

As in the blaze of day,

They rush with news of weal and wo,

To thousands far away.

But faster still than tidings borne

On that electric cord,

Rise the pure thoughts of him who loves

The Christian’s life and Lord —

Of him who taught in smiles and tears

With fervent lips to pray,

Maintains his converse here on earth

With bright worlds far away.

Ay! though no outward wish is breath’d,

Nor outward answer given,

The sighing of that humble heart

Is known and felt in Heaven; —

Those long frail wires may bend and break,

Those viewless heralds stray,

But Faith’s least word shall reach the throne

Of God, though far away.

Alton Telegraph and Democratic Review (Alton, Illinois) Mar 17, 1848

Discontented People.

Philosophers have a good deal to say about the blessings of contentment, and all that sort of thing. Nothing, however, can be more uncalled for. Contentment is the parent of old fogyism, the very essence of mildew and inactivity. A contented man is one who is inclined to take things as they are, and let them remain so. It is not content that benefits the world, but dissatisfaction. It was the man who was dissatisfied with stage-coaches that introduced railroads and locomotives. It was a gentleman “ill at ease” with the operations of mail wagons who invented the magnetic telegraph. Discontent let Columbus to discover America; Washington to resist George III. It taught Jefferson Democracy; Fulton how to build steamboats; and Whitney to invent the cotton gin. Show us a contented man, and we will show you a man who would never have got above sheep skin breeches in a life-time. Show us a discontented mortal, on the contrary, and we will show six feet of goaheaditiveness that will not rest satisfied till he has invented a cast iron horse that will outrun the telegraph.

Alton Daily Telegraph (Alton, Illinois) Jul 13, 1853

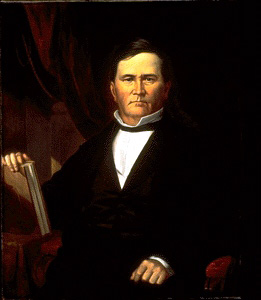

The First Telegraph.

In 1844 when Professor Morse petitioned Congress to appropriate $30,000 to enable him to establish a telegraph between Washington and Baltimore, Ex-Governor David Wallace, of this State, was a member of the committee on ways and means, to which the petition was referred, and gave the casting vote in its favor. The Whig members of the committee all voted for the measure, and the Democratic members all opposed it. The members who voted with Gov. Wallace were Millard Fillmore, Joseph R. Ingersoll, of Pa., Tom Marshall, of Kentucky, and Sampson Mason, of Ohio. Those who voted against it were Dixon H. Lewis, of Alabama, Frank Pickens, of South Carolina, Charles G. Atherton, of New Hampshire, and John W. Jones, of Virginia.

The Indianapolis News says:

“Gov. Wallace’s vote for the appropriation defeated him the next fall when he ran again for Congress. His opponent was Wm. J. Brown. He was, I’ve been told, a shrewd Democratic politician — the father of Austin H. Brown. The Governor and Mr. Brown stumped the district together, and Mr. Brown, all through the campaign, used as his most effective weapon, against his Whig opponent, the fact that he had voted for this appropriation. Pointing his finger at the Governor, he would say, ‘and the man who now asks you for your votes has squandered $30,000 of the people’s money, giving it away to Professor Morse for his E-lec-tro mag-net-ic Tell-lie-graph,’ with a most ludicrous drawl on the word telegraph. With the rough backwoodsmen, and even the people of the towns, the telegraph in that day was considered some sort of a trick or humbug; and many of Mr. Wallace’s staunchest supporters feared there was something wrong in the old gentleman’s head when they heard from his own lips that he really had voted the subsidy. One honest old Shelby county farmer, Mr. Wallace said, took him by the hand and looked into his face with the tenderest pity. Finally his lip quivered, and the tears fell as he sobbed out, ‘Oh, Davy, Davy, how could you ever vote for that d—-d magnetic telegraph.'”

The bill did not pass the Senate until the last night of the session. The story of its passage by that body has been often told, but will bear repeating. We clip the following from a scrap book’ without knowing the name of the author:

There were only two days before the close of the session; and it was found, on examination of the calendar, that no less than one hundred and forty-three bills had precedence of it. Professor Morse had nearly reached the bottom of his purse; his hard-earned savings were almost spent; and, although he had struggled on with undying hope for many years, it is hardly to be wondered at that he felt disheartened now. On the last night of the session he remained until nine o’clock; and then left without the slightest hope that the bill would be passed. He returned to his hotel, counted his money, an found that after paying his expenses to New York, he would have seventy-five cents left. That night ne went to bed sad, but not without hope for future; for, through all his difficulties and trials, that never forsook him. The next morning, as he was going to breakfast, one of the waiters informed him that a young lady was in the parlor waiting to see him. He went in immediately, and found that the young lady was Miss Ellsworth, daughter of the Commissioner of Patents, who had been his most steadfast friend while in Washington.

“I come,” said she, “to congratulate you.”

“For what?” said Professor Morse.

“On the passage of your bill,” she replied.

“Oh, no; you must be mistaken,” said he. “I remained in the Senate till a late hour last night, and there was no prospect of its being reached.”

“Am I the first then,” she exclaimed joyfully, “to tell you?”

“Yes, if it is really so.”

“Well,” she continued, “father remained till the adjournment, and heard it passed; and I asked him if I might not run over and tell you.”

“Annie,” said the Professor, his emotion almost choking his utterance, “the first message that is sent from Washington to Baltimore, shall be sent from you.”

“Well,” she replied, “I will keep you to your word.”

While the line was in process of completion, Professor Morse was in New York, and upon receiving intelligence that it was in working order, he wrote to those in charge, telling them not to transmit any messages over it till his arrival. He then set out immediately for Washington, and on reaching that city sent a note to Miss Ellsworth, informing her that he was now ready to fulfill his promise, and asking her what message he should send.

To this he received the following reply:

WHAT HATH GOD WROUGHT.

Cambridge City Tribune (Cambridge City, Indiana) Jan 1, 1880

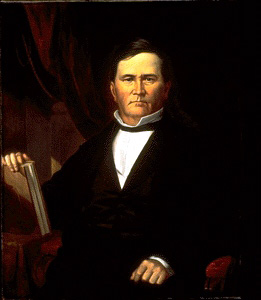

Image of Sam Houston from Son of the South

MORSE OFFERED HIS TELEGRAPH TO TEXAS STATE

AUSTIN, Texas, Aug 5. — Samuel F.B. Morse offered the Republic of Texas his invention of the electro magnetic telegraph in 1828, but the offer never was accepted, according to a letter by Mr. Morse found in the state library.

The letter, dated 1860, was addressed to General Sam Houston, then governor of Texas, and withdrew the offer, which had been more than twenty years before General Houston was president of the Texan republic. The communication was written from “Po’Keepsie”, taken by librarians to be Poughkeepsie, New York. It is dated August 9, 1860. Starting with “May it please your excellency” the letter read:

“In the year of 1838 I made an offer of gift of my invention of the electro-magnetic telegraph to Texas, Texas being then an independent republic. Although the offer was made more than twenty years ago, Texas while an independent state, nor since it has become one of the United States, has ever directly or impliedly accepted the offer. I am induced, therefore, to believe in its condition as a gift it was of no value to the state, but on the contrary has been an embarrassment. In connection, however, with my other patent, it has become for the public interest as well as my own, that I should be able to make complete title to the whole invention in the United States.

“I, therefore, now respectfully withdraw my offer then made, in 1838, the better to be in a position to benefit Texas, as well as the other states of the Union.

“I am with respect and sincere personal esteem

“Your Obedient Servant,

“Samuel F.B. Morse.”

Librarians are looking for the letter of 1838 offering the electro-magnetic telegraph to Texas. They are also seeking to find out what “other patent” Mr. Morse spoke of.

Ada Weekly News (Ada, Oklahoma) Aug 10, 1922

This Standard Gasoline advertisement ran in the Abilene Reporter News in 1937